Sorry, nothing in cart.

Renal Colic: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

- By admin

- |

- Uncategorized

- |

Renal colic is one of the most intense and distressing types of pain a person can experience. It occurs when a kidney stone obstructs the urinary tract, causing severe, cramping pain that radiates from the flank to the lower abdomen or groin. Although the pain can be excruciating, renal colic is a treatable condition. Understanding its causes, symptoms, and treatment options helps in early detection and effective management.

What is Renal Colic?

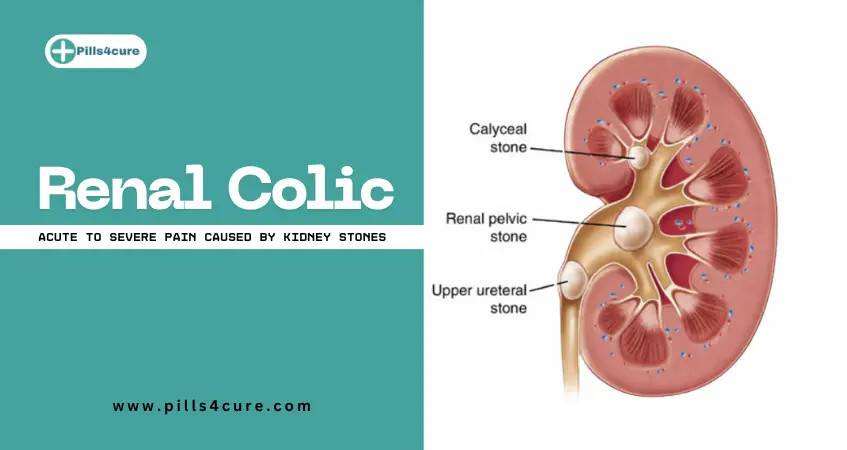

Renal colic is a type of acute pain spasmodic pain that arises due to the obstruction of urine flow in the urinary tract, most commonly caused by kidney stones (renal calculi). The blockage leads to increased pressure within the kidney and ureter, triggering intense pain. The pain usually comes in waves and may fluctuate in intensity as the stone moves through the ureter.

Renal colic is not a disease itself, but a symptom of an underlying condition, most frequently urolithiasis (kidney stones). Other less common causes include blood clots, sloughed papilla, or tumors obstructing the urinary flow.

Causes of Renal Colic

The primary cause of renal colic is obstruction of urine flow. The following are the main causes:

-

Kidney Stones (Urolithiasis):

The most common cause. Stones composed of calcium oxalate, uric acid, or cystine can form in the kidneys and get lodged in the ureter, leading to obstruction and pain. -

Blood Clots:

Occasionally, bleeding in the urinary tract can form clots that block urine flow. -

Ureteral Strictures:

Narrowing of the ureter due to injury, infection, or previous surgeries can restrict urine passage. -

Tumors:

Masses in the kidney, bladder, or ureter may compress or block urine flow. -

Sloughed Papilla:

In rare cases, parts of kidney tissue (renal papillae) detach and obstruct the ureter.

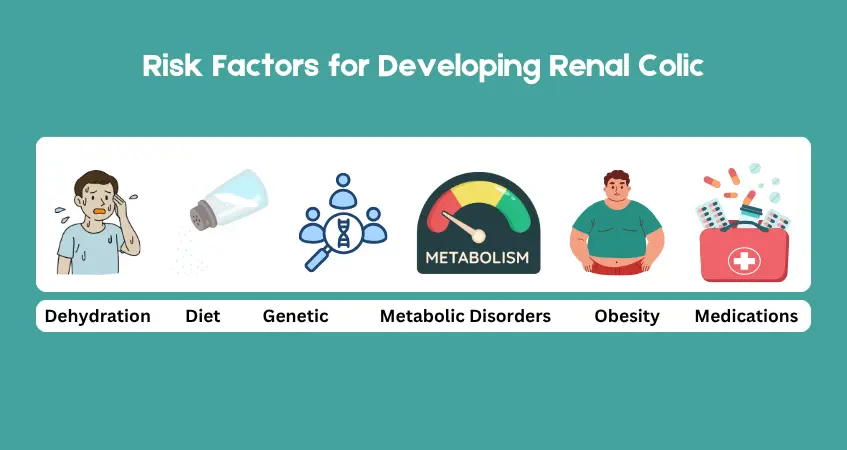

Risk Factors for Developing Renal Colic

Certain factors increase the likelihood of developing kidney stones and, consequently, renal colic:

-

Dehydration: Low water intake leads to concentrated urine, increasing stone formation risk.

-

Diet: High intake of salt, oxalate-rich foods (spinach, nuts), or animal protein.

-

Genetic Predisposition: Family history of kidney stones.

-

Metabolic Disorders: Conditions like hyperparathyroidism, gout, or renal tubular acidosis.

-

Obesity: Higher body weight is linked to altered urine chemistry.

-

Medications: Some drugs, like diuretics or antacids, may promote stone formation.

Symptoms of Renal Colic

Renal colic pain typically begins suddenly and can vary in severity. Common symptoms include:

-

Severe Flank Pain:

Sharp, cramping pain felt in the back, side, or lower abdomen. It often radiates toward the groin. -

Wave-Like Pain (Colicky Nature):

Pain comes in waves, with intervals of relief as the stone moves. -

Nausea and Vomiting:

The severe pain can trigger nausea and vomiting reflexes. -

Hematuria (Blood in Urine):

Urine may appear pink, red, or brown due to irritation of the urinary tract lining. -

Frequent Urination and Urgency:

The person may feel the need to urinate frequently or urgently, especially if the stone is near the bladder. -

Fever and Chills:

These may indicate a urinary tract infection (UTI) associated with the obstruction and should be treated as an emergency.

Types of Renal Colic Pain

Renal colic pain is classified based on the location of the obstruction:

-

Upper Ureteric Colic: Pain in the flank and upper abdomen.

-

Mid-Ureteric Colic: Pain radiates to the lower abdomen.

-

Lower Ureteric Colic: Pain moves toward the groin, inner thigh, or testicles/labia.

Diagnosis of Renal Colic

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment. A healthcare provider may use several tests and imaging techniques:

-

Medical History and Physical Examination:

The doctor will inquire about pain characteristics, urinary symptoms, and previous stone history. -

Urinalysis:

Detects the presence of blood, infection, or crystals that indicate stone type. -

Blood Tests:

To check kidney function, infection markers, or high calcium and uric acid levels. -

Imaging Studies:

-

Non-contrast CT Scan: Gold standard for identifying stones and their location.

-

Ultrasound: Useful for pregnant women or when radiation exposure must be avoided.

-

X-ray (KUB): Helps visualize certain types of stones, though less sensitive.

-

Treatment of Renal Colic

Treatment depends on the stone’s size, location, and severity of symptoms. The goal is to relieve pain, remove the obstruction, and prevent recurrence.

1. Pain Management

Pain control is the first step:

-

NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs): Such as ibuprofen or diclofenac help reduce pain and inflammation.

-

Opioids: Used in severe cases when NSAIDs are insufficient.

-

Antispasmodics: May relieve ureteral muscle spasms and ease stone passage.

2. Hydration

Increased fluid intake helps flush out small stones (usually <5mm). Patients are encouraged to drink 2–3 liters of water daily unless contraindicated.

3. Medical Expulsive Therapy

Medications such as alpha-blockers (Tamsulosin) or calcium channel blockers may relax ureteral muscles, allowing stones to pass more easily.

4. Surgical or Minimally Invasive Procedures

If the stone is large or fails to pass naturally, medical procedures are required:

-

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL):

Uses sound waves to break stones into smaller fragments. -

Ureteroscopy:

A thin scope is inserted into the urethra to locate and remove or fragment stones. -

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy:

Used for large stones; a small incision is made in the back to remove stones directly from the kidney. -

Stent Placement:

A temporary stent in the ureter helps relieve obstruction and promote drainage.

Complications of Untreated Renal Colic

If not managed promptly, renal colic can lead to serious complications, including:

-

Hydronephrosis: Swelling of the kidney due to trapped urine.

-

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI): Obstructed urine provides a medium for bacterial growth.

-

Kidney Damage: Prolonged obstruction can impair kidney function.

-

Sepsis: A life-threatening infection that requires emergency treatment.

Prevention of Renal Colic

Preventing kidney stones is key to avoiding future episodes of renal colic. The following strategies can help:

-

Stay Hydrated:

Drink plenty of water throughout the day to dilute urine. -

Maintain a Balanced Diet:

Reduce salt and animal protein intake, and limit foods high in oxalate (e.g., nuts, spinach, tea). -

Monitor Calcium Intake:

Don’t restrict calcium excessively — normal dietary calcium actually prevents stone formation. -

Limit Sugar and Soft Drinks:

High fructose intake can increase stone risk. -

Regular Medical Check-ups:

Those with a history of stones should undergo periodic urine and imaging tests.

When to Seek Medical Help

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience:

-

Severe pain that doesn’t subside with rest or medication.

-

Persistent vomiting or inability to keep fluids down.

-

Fever, chills, or signs of infection.

-

Blood in urine or difficulty urinating.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Renal Colic

Q1. What is renal colic?

Ans: Renal colic is a type of severe, cramping pain caused by an obstruction in the urinary tract, most commonly due to kidney stones. The pain usually begins in the flank or lower back and may radiate to the groin as the stone moves through the ureter.

Q2. What causes renal colic pain?

Ans: The main cause of renal colic is kidney stones blocking the urinary tract. Other causes include blood clots, ureteral strictures, or tumors that restrict urine flow. The blockage increases pressure inside the kidney, leading to intense pain.

Q3. What are the symptoms of renal colic?

Ans: Common symptoms include sharp flank pain, blood in urine, nausea, vomiting, frequent urination, and pain radiating to the groin. In some cases, fever and chills may occur if there is an associated urinary infection.

Q4. How long does renal colic last?

Ans: The duration depends on the size and location of the stone. Mild cases may resolve within a few hours to days, while larger stones may cause intermittent pain lasting several weeks until treated or removed.

Q5. How is renal colic diagnosed?

Ans: Doctors diagnose renal colic using urine tests, blood tests, and imaging studies such as CT scans, ultrasound, or X-rays (KUB) to identify the stone’s size, location, and possible complications.